(This is the twenty-fourth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Kim.)

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s recent passing has made me keenly cognizant that being a wallflower is not an option when any of us could fall off the wall. (The poor man never got to finish Re: Joyce, his wonderful podcast on Ulysses.) So here we go.

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s recent passing has made me keenly cognizant that being a wallflower is not an option when any of us could fall off the wall. (The poor man never got to finish Re: Joyce, his wonderful podcast on Ulysses.) So here we go.

What I have wondered during this Joyce-populated reading period is whether one should even attempt to match Jimmy Jimmy Jo Jo Bop’s unquestionable erudition, for this is the kooky bodkin he has wielded before readers. A Wake expert once told me that fencing with this book is comparable to being diagnosed with a disease. A good friend, as deeply moved by Ulysses as I am, told me that he never bothered with Finnegans Wake. I asked why. He said that he refused to play James Joyce’s game. I replied, “Yes, but in the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, you are missing out on some marvelous puns and portmanteaus and the limitless richness of an obscurant dreamscape!” But I do see my pal’s point. Where Ulysses provides us with an invitational beauty to be treasured and reconsidered at nearly any time in life, Finnegans Wake is the loutish intoxicating charmer for the young, the book declaring itself the cleverest in the room, the novel above all novels that says, “Well, if you really love literature…”

In attempting to come to terms with the Wake, I certainly don’t wish to align myself with such execrable anti-intellectual oafs like Dan Kois, who see the joyful act of great art mesmerizing a daredevil reader as something akin to eating cultural vegetables. I have enjoyed longass offerings from Marugerite Young, Samuel R. Delany, Laurence Sterne, Umberto Eco, Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, Gertrude Stein, Mark Z. Danielewski (see The Familiar, the fifth of its twenty-seven volumes will be released in October), and William T. Vollmann, but none of this could prepare me for the Wake. Finnegans Wake is worth the cerebral sweat if you are willing to sign up for the gym package, which involves knowing a little German, Gaelic, and French, familiarizing yourself with Vedic commentary, reading up on Giambattista Vico and Irish history, and doing your best to encourage and resist the urge to plunge further. It is certainly difficult to argue against the Wake‘s enchanting use of language. But if cleverness — even from a bedazzling and often sprightly brainiac such as the Wake — involves adjusting one’s mind and heart entirely to that of the author, there is unquestionably a form of literary tyranny involved. On the other hand, the Wake, unlike any other book I have ever read, does test the limits of what we’re willing to know and how you can live with not knowing. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realize that reading the Wake aloud and letting much of the esoterica wash over you is the best way to approach it and to love it. The only sane option is to accept that you will never know all the answers, that Joyce is smarter than you, and to enjoy the experience.

The book left me baffled, delighted, and often drove me mad. I am not sure that I want to read it again, although who’s kidding whom? I probably will. Finnegans Wake often felt like some bright and charming friend with benefits who texts you at 2AM, asking if you’re down to hook up, only to make you its bottom and leaving you cooking breakfast the next morning as your sexy lover basks in languor in your bed, singing pitch-perfect melodic ballads and cracking the smartest jokes in German. You sometimes wonder if you’re receiving any pleasure in a consummation that was supposed to be fun and spontaneous. Did I catch a case of the ten thunderclap words sprinkled throughout the book (Adam Harvey has kindly made YouTube videos on how to pronounce these) or merely the clap? These carnal metaphors on a book that essentially builds a dreamy narrative from an episode of sexual humiliation are no accident. Like Tinder, Finnegans Wake is a young man’s game. I would recommend attempting it before the age of forty, when there is still the time and the hunger to unravel the arcane wisecracking. Perhaps my mistake was reading this book on both sides of forty, with one foot steeped in bountiful possibility and the other more aware of mortality and the grave. My earlier plunges were largely felicitous. My subsequent belly flops were coated with the minor sting of missing out on something vital in the real world. And given the choice between staying home with the Wake or having a fun night out, it was a fairly easy decision. Many unreportable evenings later, I still believe I made the right choice. But how could any sensible reader not be wowed and enamored by Joyce’s uncompromising commitment to a difficult aesthetic?

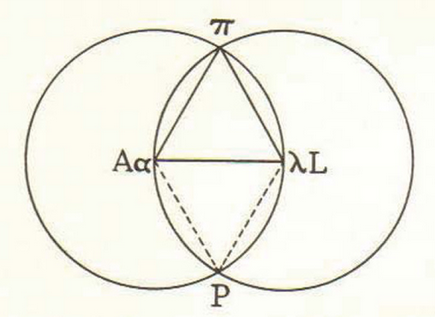

All told, I worked my way through this intoxicating and frustrating melange in its full inimitable entirety twice, returning to the beginning of the Earwicker saga and then rereading other bits out of sequence, such as the mirthful and genuinely pleasurable showdown between Shaun and Shem in Book I, Chapter 7, which is among my favorite parts of the book. I can certainly follow the primary points of this “commodious vicus of recirculation,” even if the music of words usually triumphs over narrative coherence, which is often sandbagged altogether by later events such as Shaun’s ever-shifting identity. While I have largely enjoyed my journey, there were several points in which I cursed out Joyce for leading me down another rabbit hole. (The Dubliners’ low-key musical version of “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly? My weeks-long obsession with the Wellington Monument near the south of Dublin’s Phoenix Park? My futile attempts to learn Gaelic on Duolingo? My concern with ellipses and a surprising preoccupation for how reels of film turned upon encountering “the lazily eye of his lupis” and the diagram above? My efforts to reconcile Butt and Taff with Mutt and Jute and follow the batty Irish-American connections — extending to a few visiting American characters and the dual Dublin in Laurens County, Georgia, which Joyce cites?) It has left me to ponder in all this time if Finnegans Wake and its “futurist onehorse balletbattle pictures” were entirely worth understanding. It has left me feeling very sorry indeed for Joyce’s very patient benefactor, Harriet Shaw Weaver. The phrase “tough sledding” is an understatement.

All told, I worked my way through this intoxicating and frustrating melange in its full inimitable entirety twice, returning to the beginning of the Earwicker saga and then rereading other bits out of sequence, such as the mirthful and genuinely pleasurable showdown between Shaun and Shem in Book I, Chapter 7, which is among my favorite parts of the book. I can certainly follow the primary points of this “commodious vicus of recirculation,” even if the music of words usually triumphs over narrative coherence, which is often sandbagged altogether by later events such as Shaun’s ever-shifting identity. While I have largely enjoyed my journey, there were several points in which I cursed out Joyce for leading me down another rabbit hole. (The Dubliners’ low-key musical version of “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly? My weeks-long obsession with the Wellington Monument near the south of Dublin’s Phoenix Park? My futile attempts to learn Gaelic on Duolingo? My concern with ellipses and a surprising preoccupation for how reels of film turned upon encountering “the lazily eye of his lupis” and the diagram above? My efforts to reconcile Butt and Taff with Mutt and Jute and follow the batty Irish-American connections — extending to a few visiting American characters and the dual Dublin in Laurens County, Georgia, which Joyce cites?) It has left me to ponder in all this time if Finnegans Wake and its “futurist onehorse balletbattle pictures” were entirely worth understanding. It has left me feeling very sorry indeed for Joyce’s very patient benefactor, Harriet Shaw Weaver. The phrase “tough sledding” is an understatement.

Still, you can’t help but sympathize with a man who, buttressed by the wealth and the literary notoriety that came after Ulysses, saw his “Work in Progress” (early selections of the Wake published in journals) abandoned by many of his prominent supporters as he was going blind. Stanislaus Joyce had already become suspicious of Ulysses‘s famously difficult “Oxen of the Sun” chapter and proceeded to condemn his brother further for the bits of the Wake that had appeared in the transatlantic review and would later tell Jim to his face that his “book of the night” was impenetrable. His benefactor Harriet Shaw Weaver went along with Joyce’s new direction for a while, with Joyce providing her with a pre-Campbell skeleton key on January 27, 1925, but later that year, some printers refused to set the type for these new excerpts. And two years later, Weaver would condemn the “Wholesale Safety Pun Factory” that Joyce had wrought. Ezra Pound, the putative paragon of poetic innovation, turned on Joyce, badmouthing this “circumambient peripherization.” H.G. Wells called it a dead end. (Did Rebecca West put a burr in Herbert’s ear?) In the face of declining love, Joyce’s remaining admirers published Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress, featuring the likes of Samuel Beckett, Frank Budgen, and William Carlos Williams defending Joyce’s new direction. Beckett would write:

Here form is content, content is form. You complaint that this stuff is not written in English. It is not written at all. It is not to be read — or rather it is not only to be read. It is to be looked at and listened to. His writing is not about something: it is that something itself….When the sense is sleep, the words go to sleep….When the sense is dancing, the words dance.

It was believed that Joyce himself wrote one of the two letters of protest featured in this small volume. Certainly the voice in the letter is unmistakably recognizable:

You must not stink I am attempting to ridicul (de sac! )you or to be smart, but I am so disturd by my inhumility to onthorstand most of the impsolocations constrained in your work…

Joyce wanted to have it both ways. He both longed for recognition and was contemptuous of anyone who didn’t recognize his genius. The remarkably vanilla-minded Arnold Bennett, a troublesome gnat who I wrote about earlier and who only boorish bores like Philip Hensher now have wet dreams about, redoubled the troubling conventionalism that he had expressed for Ulysses and continued to attack Joyce in the press, which inspired Joyce to send him up as Jute.

In reading the Wake, I have often wondered if I have understood anything at all, but I cannot abide by D.H. Lawrence’s characterization of Joyce as “too terribly would-be and done-on purpose, utterly without spontaneity or real life.” For Joyce does not bore me. He merely maddens me with his demands on my time. I ken the puns in many tongues and can divine much of the history blurring into alluring verbs. Joyce’s wildly arrogant but nonetheless remarkable goal was to keep the professors arguing over enigmas and riddles for centuries. And with the Internet, he has succeeded. Finnegans Wiki is a vital companion when you first start reading and hope to know everything, until you realize that you never will. What is more important here is to feel the book, to take in its miasmic rushes and quell the urge to order mimosas when your noggin explodes from too much “folkenfather of familyans.”

In my early days of reading the Wake, I kept up a Tumblr on my notes. I filled up a five subject notebook with crazed and often indecipherable notes. And then I realized that to carry on like this was futile. It would be akin to resolving every unsolved mystery about life. The Wake contains almost as many tributaries.

Finnegans Wake is not a book to be read. It is a book to be lived, ideally with fellow travelers. So if you have a very rich and active life, there’s no getting around the need to make time for it. Fortunately, it has inspired any number of marvelous online offerings. The incredible project, Waywords and Meansigns, has performed three different musical versions of the Wake. Listening to these interpretations helped lift my spirits when I wondered if I should give up entirely (the bluesy interpretation of the pearlagraph episode near the beginning of Book II came at a time when I was about to throw my book into the wall for the seventh time). I attended a meeting of The Finnegans Wake Society of New York, which not only led me to this invaluable annotative resource, but allowed me to understand that even the smartest and most literary people imaginable could not entirely make head or tail of Joyce and that any and all interpretive suggestions were fair game.

If Joyce wrote Ulysses for people to reconstruct Dublin brick by brick after the apocalypse, then Finnegans Wake was written to reconstruct the whole of human existence, albeit a region teetering somewhere between reality and dreams. There are crazed Russian generals and discordance and recursiveness and twins and families and lust and religion and bawdiness and drinking and blasphemy, but, much like Molly Bloom’s beautifully baring “Penelope” monologue, the Wake ends with the singular motive voice of a woman:

First we feel. Then we fall. And let her rain now if she likes. Gently or strongly as she likes. Anyway let her rain for my time is come. I done me best when I was let. Thinking always if I go all goes. A hundred cares, a tithe of troubles and is there one who understands me? One in a thousand of years of the nights? All me life I have been lived among them but now they are becoming lothed to me. And I am lothing their little warm tricks. And lothing their mean cosy turns. And all the greedy gushes out through their small souls. And all the lazy leaks down over their brash bodies. How small it’s all! And me letting on to meself always. And lilting on all the time. I thought you were all glittering with the noblest of carriage. You’re only a bumpkin. I thought you the great in all things, in guilt and in glory. You’re but a puny. Home! My people were not their sort out beyond there so far as I can. For all the bold and bad and bleary they are blamed, the seahags. No! Nor for all our wild dances in all their wild din.

And then we read “A way a lone a last a loved a long the,” and feel and fall some more, and turn back to the beginning to finish the aborted sentence. And every time we run through the loop, there is laughter, marvel, something we missed, something that aggravates us, and something that makes the rest of literature feel irrelevant.