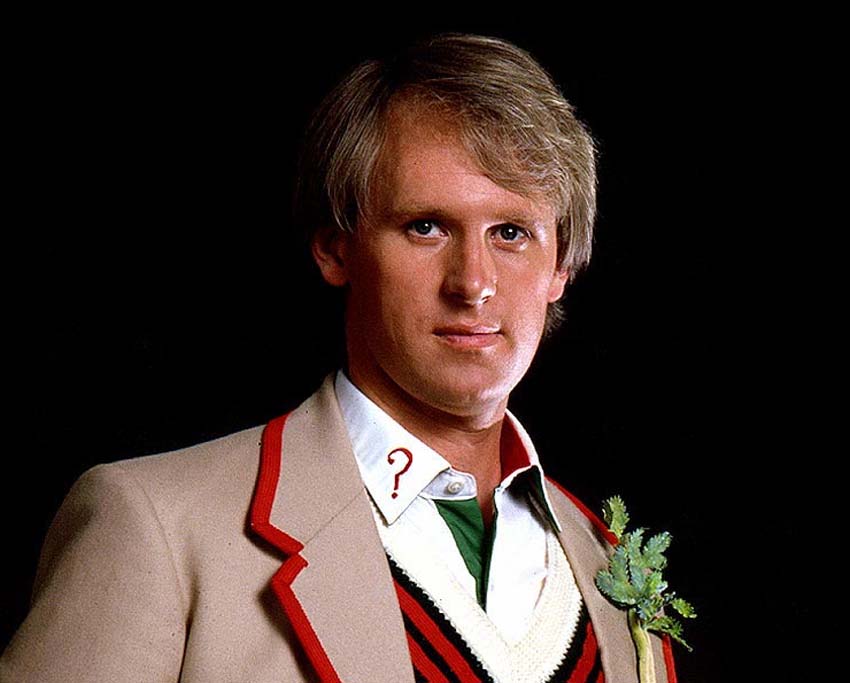

Benjamin Anastas is most recently the author of Too Good to Be True.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wrestling with failure.

Author: Benjamin Anastas

Subjects Discussed: Memoirs devoted to literary failure, Paul Auster’s Hand to Mouth, Tom Grimes’s Mentor, being inspired by Notes from Underground, measuring life through the medium of writing, seeking existential symmetry through writing, recurring images of sedans crashing into a tree, the difference between work in fiction and work in nonfiction, Brooklyn Flea vs. South Brooklyn flea markets, being confined to specific areas of Brooklyn, maintaining a literary illusion, staying in denial about gentrification or geographical change, being slow to adapt, “you” vs. “I” in a memoir, living in Williamsburg and Italy, the need to close off the world to get your work done, the pros and cons of needing to notice, the need to believe in the illusion as a creative person, writing as a ontological gamble, the stigma of not talking about the realities of being a writer, standing in a boxing ring designed for Muhammad Ali at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the Penguin/Random House merger, publishing with Amazon, talking with Jason Epstein, writing as a life going through self-inflicted hardships, why broke writers aren’t special, parental legacy, adultery as a choice, giant posters of Franzen and Eugenides, the writer’s ego, how book fairs can devastate a writer, the attenuated lifespan of a book, blurbs, why New York is an unhealthy place for a writer to live, a level playing field in which all publishing houses are equal, Brooklyn as the second most expensive place to live in the United States, publishing a celebrity journalist’s Facebook messages, Coinstar machines, the divide between the public and the private, navigating through Facebook posts, the need for reflection, the ineluctable physical demands that come with a Kindle book cover, clearing appearances of the Nominee and Marina with various legal counsel, earlier vindictive forms of Anastas’s letter to the Nominee, Dwight Garner’s hostility to the letter, the true manner in which a prize winner talks, Ali’s “It’s not bragging if you can back it up,” boasting, the blues as a shape-shifting force, writing chapters that cause you to burst into tears, what Anastas had to omit because of personal limitations, money as the stigma that has replaced sex, unknown novels being written about the financial crisis or unemployed men, the Fitzgeraldian association with the Manhattan skyline, and the many holes and changes and rebuilding in New York City**.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: There are a number of memoirs that are devoted to literary failures. I think of Paul Auster’s Hand to Mouth. I think of Tom Grimes’s Mentor. And I think that there’s something about reading a book about literary failure that’s kind of akin to looking at the mirror and seeing the sagging and aging body and so forth. This leads me to ask what it must feel like to write such a thing, to expose something that is so identified with books and so identified with failure in book form. How do you contend with the notion of shame or humiliation? Or do you have no shame?

Anastas: Do I have no shame? Well, clearly, I actually have no shame. (laughs) I never set out to write a memoir. I actually have always been kind of anti-memoir in my writing life. I’ve written screeds against them. My first novel, I thought of it as a kind of Russian tract against the memoir when I was writing it and publishing it. I was very much influenced by Dostoevsky and Notes from Underground, which was a response to — I don’t remember the name of the tract*, but it was a response to this contemporary political tract. So I was trying to use the novel in my first book as an answer to what I thought then was the memoir craze. But of course the memoir craze has just spread and metastasized. And we live in a memoir society. But anyway, I ended up writing a book honestly because I really had no other choice.

Correspondent: You had no other choice?

Anastas: Well, seriously, I mean, I’d been trying to write fiction for a long time and I just hadn’t been working. I would either abandon projects 100 pages in or I would just edit them to death so there was really nothing there. And the circumstances of my life had gotten so bad that I couldn’t really do the necessary work of imagining. Every time I sat down to write, all I could think about was, well, god, how am I going to pay the rent this month? Or, jeez, is my girlfriend going to leave me because I’m so broke? Or what am I going to do about my child support payment coming up on the 15th? That’s all financial stuff. But there was also this overwhelming sense of “How did this happen to me?” How did I find myself here?

Correspondent: Did you feel that you were a victim and that you needed to memorialize this notion of “How did I get here?” Did it come from a sense of victimhood, do you feel?

Anastas: No. Definitely not victimhood. I mean, what was really interesting to me was trying to figure out — well, the book moves in two directions simultaneously. The first is it moves forward in time, which I was literally writing in real time. How am I going to get myself out of this mess? How am I going to find a job? How am I going to keep my girlfriend? How am I going to keep on seeing my son as well? Because I absolutely want to.

Correspondent: So you weren’t a fact checker at the beginning of writing.

Anastas: No. I wasn’t. I started writing the book in the fall of 2010. And I was just about to hit financial rock bottom. And it was the kind of situation where people had stopped answering my emails. The kind of things that I had done to make money had all disappeared.

Correspondent: You weren’t led past the velvet rope in any form. (laughs)

Anastas: (laughs) Exactly. Exactly.

Correspondent: So why did you feel — I guess you felt the need to grapple to the closest reality at hand. And that was the only way to actually deal with it. I mean, there’s actually one line where you say, “How much of our lives do we write? And how much of them are written for us?” And I’m wondering why you feel life has to be measured by how it is documented or how it is written about or how it is chronicled and how this was a way for you to deal with this really sordid rock bottom existence that is there at the very beginning of the book.

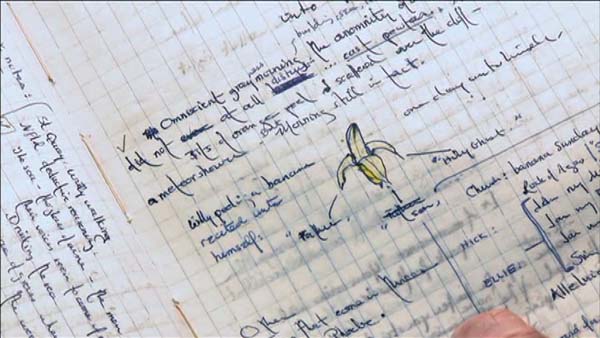

Anastas: Well, it’s funny. I used the phrase “write.” “How much of our lives do we get to write?” Of course, that’s how I think about life. Because I am a writer. But I really meant that metaphorically in the sense of how much of our own lives do we get to control. How much agency do we have? And how much of it is stuff that we’ve inherited? So there were two things simultaneously happening in the book. The first is that I’m trying to figure my way out of this mess and actually find work and try to keep my relationship alive and keep my relationship with my son alive. And also at the same time try to restore my relationship to writing by going into my son’s room with a notebook everyday with a pen. Just writing this book or the pages that began this book. Writing them out in longhand. And the second thing I was trying to do was go back in time. All the way back to the beginning. To my first memories. To try and figure out, well, how much of where I found myself is due to experiences I had when I was young? How much of it can be traced to be formative experiences I had when I was three years old? Including the really bad childhood therapy, which gives the book its title. So more than assigning blame, more than claiming victimhood for myself, it’s a way to try and create connections, to find where the symmetry is. Because I did feel like my life was weirdly symmetrical. Like I had been returned to the state that was very much like my earliest beginnings.

Correspondent: But it’s interesting that you view your life from this image of premonition throughout the book. The idea of the sedan that’s running into a tree, which then starts to have applicability to other incidents later on. Or even “I lost my marriage going down a glass elevator.” There is a sense of personal responsibility we all have, that we can in fact take action to if not inform that premonition then to also throw a few curve balls at the inevitable. Why do you seem to default, at least in this book, towards the premonitory? Or the “Oh, well my life has this trajectory that’s just going to play out this way”?

Anastas: Because I think that, as I said, I was trying to trace the moments of symmetry and put the pieces of this life that had been broken up into large pieces that were kind of dangling all over the apartment and hung over the railing and all this kind of stuff. I wanted to put it all together and figure out how I got to this place in life. And to me, that’s being active. That’s not being passive and saying, “Oh, life has done these things to me.” I haven’t been an equal part in saying, “Oh, life, how could you!” To me, that feeling never really entered into it. It was more a sense of taking what I do have, which is a knowledge of writing, a knowledge of books, and some measure of talent and trying to use those to knit back together a life that had broken to pieces.

Correspondent: It’s fascinating to me that you couldn’t actually approach this dilemma through fiction or that there was difficulty. You said that you were writing fiction that was too edited. Did you just really need to have an extremely broken place with which to turn out something as a writer? What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction to you? I’m really curious about this. Why can’t you approach fiction in the same way that you approach nonfiction? Which is like “Here I am. I’m kind of responding to the broken place I’m in, but I’m going to write my way out of it.”

Anastas: Well, that’s what I had been able to do my entire writing life. Up until the last four or five years. Obviously your life informs your fiction, even if the characters you’re writing about and the time that they live in has nothing to do with where you are. You always have some kind of overwhelming feeling that you’re trying to capture. And the feeling often comes from your immediate set of circumstances. You just lend it to somebody else. But I think just because of the dire state of my circumstances and because of the ways I’d failed as a fiction writer over the past five years, I just couldn’t do it anymore. And I had to, for this book anyway, I had to write it straight. It was a reality experiment. I was writing about things as they were happening. Which was incredibly rewarding in a lot of ways. But it was also so I could get the immediate satisfaction.

* — It was Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s What Is to Be Done?, which in turn was a response to Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons.

** — Please note that this conversation was recorded before Hurricane Sandy.

The Bat Segundo Show #495: Benjamin Anastas (Download MP3)