Stewart O’Nan appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #454. He is most recently the author of The Odds. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #161. You can also read our lengthy conversation by email in 2011. This 2012 talk was recorded before a live audience at McNally Jackson. My gratitude to Michele Filgate, Langan Kingsley, Holly Watson, and, of course, Stewart O’Nan for their help in putting this event together.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Inexplicably hungering for Wendy’s hamburgers.

Author: Stewart O’Nan

Subjects Discussed: [forthcoming later this afternoon]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Niagara Falls. Here is a location that’s loaded with all sorts of associations. Joyce Carol Oates wrote a book there.

O’Nan: The Falls.

Correspondent: Yes, exactly.

O’Nan: Yes, I was introduced the other night as “the author of The Falls.”

Correspondent: (laughs)

O’Nan: And I was like, “Not that prolific.” Not nearly.

Correspondent: (laughs) Well, you are churning them out one a year.

O’Nan: Oh thank you. Churning them out. You said cranking before.

Correspondent: Crafting! Cranking, churning. All right. But they’re short! They’re short.

O’Nan: They’re tiny.

Correspondent: There’s craftsmanship in there. Don’t worry.

O’Nan: I understand.

Correspondent: But I’m wondering. You’re taking a location that’s loaded with all sorts of cultural baggage. There’s that Marilyn Monroe/Joseph Cotten film.

O’Nan: Gotta love it.

Correspondent: But I’m wondering. Here you are taking two characters and putting them in a touristy location. I’m wondering if you did that to work up against limitations and see what kind of behavior you could mine based off of that. I’m wondering why you chose this. What was the process of selecting the Ice Bridge or the details of the customs location? What went into nailing Niagara?

O’Nan: Well, it’s a ready made stage. Usually when I take on an area or a setting, it’s virgin territory in a way. Conneaut, Ohio. Kingsville in Songs for the Missing. No one’s ever written about that in any kind of novel. Western Pennsylvania. Butler, PA in 1974. So I always say I’ve written the best Butler, Pennsylvania novel ever written.

Correspondent: (laughs)

O’Nan: Or Avon, Connecticut. Usually these are overlooked places. Like New Britain, Connecticut, that Last Night at the Lobster takes place in. I write in that interzone, that nowhere America of strip malls. It has been kicked around forever. But in the new book, I thought, let’s focus solely on the characters and put them on a stage that everybody knows. So I don’t have to do that disorienting, here is the place that you don’t know and now I’m going to tell you about it. So I had a little less responsibility to the setting and I could spend a little bit more time on the characters.

Correspondent: I have to ask you about the odds as chapter headers for all of these. Some are, in fact, true. “Odds of a black number coming up in roulette: 1 in 2.06.” I Wikipediaed that. Some are unscientifically true. “Odds of a marriage proposal being accepted: 1 in 1.001.” So I’m wondering. How many odds did you collect? I mean, I’m wondering if you were sitting on a bunch of odds sets.

O’Nan: Yes. Yes.

Correspondent: You were?

O’Nan: Yes, I was. And I was trying to figure out: How do I weave these into the book and what effect are they going to have when I get them in there? And they seemed to me to work. When I thought of using them rather than chapter headings, in the way I did with, say, Emily or in Songs of the Missing, I saw them as how the chapter headings are in something like Blood Meridian or in, say, 19th century fiction work, which is “In this chapter I am eaten by sharks.” And before you even get into the chapter, you’re like, “Oh sharks! This could be cool!” So it kind of brings the reader and it gives them an expectation of what may happen in this chapter. Not necessarily has to happen. But it may happen. The odds of dying in a bus crash. Whoa! There might be a bus crash. I’ll stick around and find out.

Correspondent: It’s interesting. Because here you are in one sense messing with the reader for the first ten pages, repelling them, and then on this, you’re subverting their expectations. It’s actually, “Ooh! I want to continue to read this chapter.”

O’Nan: Well, you hope.

Correspondent: What of this bipolar approach to fiction writing?

O’Nan: Flannery O’Cononr. Flannery O’Connor said, “Distract them and hit them over the head.” Absolutely right. Absolutely right. Give them a reason to come into the place. A Prayer for the Dying. The opening sections are very — it’s a terrible thing to say, very beautifully written. I use the language. I make the beauty of the language a key thing to hang into. And so the reader gets rewarded somehow. And by the time they have to go through the book, they’re kind of stuck. They’re like, “Well, I don’t really want to hang around and watch this guy go crazy while I’m inside of his mind.” Well, it’s too late. So like Poe, say, in “The Black Cat.” Once you get them in the door, then after a certain point, they’re kind of yours. They have to follow along. Or you hope so. You always hope so.

Correspondent: I’m curious if the odds sets actually were methods for you to riff off of Art and Marion. If you were stuck at a certain place. Is this a point? I mean, you’re a former engineer. I presume that this was either heavily designed. Or were there false starts? And did the odds help you in anything?

O’Nan: No. There weren’t a whole lot of false starts. I knew the characters very well before I opened up. It’s also a small novel. It’s very much sort of a drawing room novel in a way. It’s the one weekend. You’ve got the unity of place. The unity of time. You’ve got a lot of pressure on them from the memories. This is their second honeymoon. They’re in Niagara Falls. And you have the time pressure of, well, at some point, they’re going to have to put their money down on the wheel. And they’re always kind of at odds with one another. They’re always picking at one another. So I had a lot to work with. The plates were already spinning when I started getting into it.

Correspondent: I wanted to also ask you. One interesting thing that you also do with Marion is body image. She doesn’t like Art to see her undress. And in one of the passages you’re going to read tonight, the only thing you mention is her stomach. We actually don’t really know what she looks like physically. So I’m wondering if this is a method for you to not reveal certain details to the reader or this reflects your relationship to the reader. Is this your way to protect your own characters? To not divulge all? Or is this your way to encourage judgment? Perception on the reader’s behalf?

O’Nan: This is more to encourage the reader to join in the process of creating the work. And I don’t say what the character looks like unless it’s really necessary to the arc of the story there. So what the characters look like is completely up to the reader there. And I leave judgment to the reader. I don’t try to steer the reader too much in terms of who’s good, who’s bad, who’s right, who’s wrong. And it’s always sort of that inkblot that shows how generous the reader can be or how, on the flip side, how stingy they can be. “I hate Marion. I hate her so much.” It’s like, “Easy there, lady. Easy there.”

Correspondent: Have you had this happen before?

O’Nan: Oh yeah.

Correspondent: Wow. Really?

O’Nan: In Wichita of all places.

Correspondent: Wichita!

O’Nan: “I didn’t like her.” Well, that’s good. That’s your prerogative. That’s fine. That’s you.

Correspondent: You know, one of the interesting things — I’ve read a number of reviews of this book. And they actually don’t mention, for example, Karen or these two characters who are having affairs with the couple. And I’m curious about this. Maybe this relates to this issue of giving the reader something. Maybe they don’t want to talk about this aspect of Art and Marion. What do you think of this?

O’Nan: Yeah. I think they want to key more on Art and Marion and just say, “Look, there are problems in the marriage.” And this is how they work them out over this weekend. Or don’t work them out.

Correspondent: Inevitably, because you do deal with Heart, I have to bring up celebrity gossip.

O’Nan: Heart.

Correspondent: So in late 2010, Nancy Wilson and Cameron Crowe initiated divorce proceedings. It was a great shocker to certain waves.

O’Nan: So sad. They had everything going for them, didn’t they? They did.

Correspondent: Yeah. I’m wondering if you including the Heart concert before or after you heard this news. Or if you possibly predicted this dissolution in anyway. I mean, what of this?

O’Nan: I don’t know.

Correspondent: Some sort of angle here.

O’Nan: No. I don’t know. It’s accidental subtext, I guess. I guess it happens from time to time.

Correspondent: Another silly question. Wendy is a character. And I have to ask you, and I know this is really pedantic, but I have noticed in all of your books — nearly all of your books — there’s a moment where someone eats Wendy’s. A Wendy’s hamburger.

O’Nan: Really?

Correspondent: But not, not in The Odds. The last time I saw this was Last Night at the Lobster. There was a Wendy’s moment. It was the Stewart O’Nan Wendy’s moment!

O’Nan: He doesn’t go to Wendy’s.

Correspondent: Oh, he doesn’t go to Wendy’s?

O’Nan: He decides not to go to Wendy’s.

Correspondent: But he does actually consider it!

O’Nan: This is a climax. This is a climax in an actual work of fiction. “Want to go to Wendy’s? Nah.”

Correspondent: Do you eat at Wendy’s quite a bit?

O’Nan: No. Maybe that’s it. Maybe I want to eat at Wendy’s more. I can see my biographer doing a lot on Wendy’s now. A map of all the Wendy’s around my house.

(Photo credit: Here)

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently

Kandel: I think what is really so important is, as you pointed out, that there was an interaction between science, literature, and arts that was really unusual. And this began with the School of Medicine, which had great leadership at that time. Under the leadership of a guy called Rokitansky who introduced modern scientific medical practice by developing clinical/pathological correlations to a more systematic way than it had ever been. He felt that when you listened to a patient’s heart and you hear an abnormal sound, you don’t know which valve it’s coming from or exactly what is the disorder of the valve. And so he collaborated with a clinician. And the clinician described the patient’s sounds from the heart and the lungs in great detail. But if the patient died, they collaborated together to do an autopsy on him to figure out exactly what valve was involved and how. And that gave rise to the scientific medicine we now practice. And Rokitansky realized that the truth is often hidden from the surface. And you have to go deep below the surface to get there.

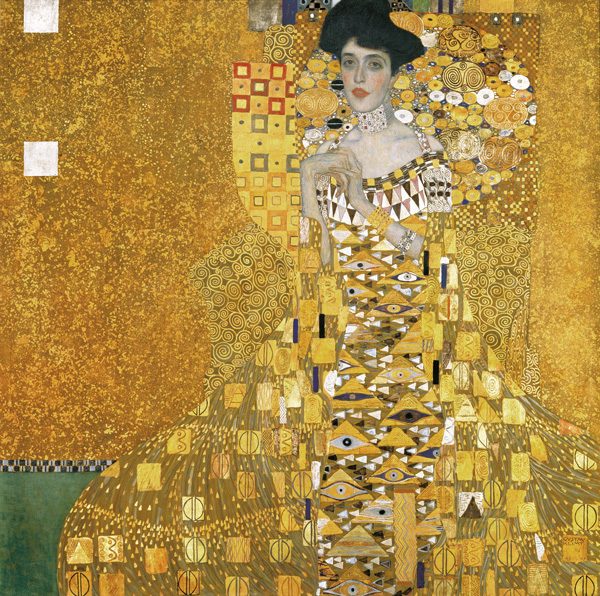

Kandel: I think what is really so important is, as you pointed out, that there was an interaction between science, literature, and arts that was really unusual. And this began with the School of Medicine, which had great leadership at that time. Under the leadership of a guy called Rokitansky who introduced modern scientific medical practice by developing clinical/pathological correlations to a more systematic way than it had ever been. He felt that when you listened to a patient’s heart and you hear an abnormal sound, you don’t know which valve it’s coming from or exactly what is the disorder of the valve. And so he collaborated with a clinician. And the clinician described the patient’s sounds from the heart and the lungs in great detail. But if the patient died, they collaborated together to do an autopsy on him to figure out exactly what valve was involved and how. And that gave rise to the scientific medicine we now practice. And Rokitansky realized that the truth is often hidden from the surface. And you have to go deep below the surface to get there.  Correspondent: Sure. Well, let’s talk about Egon Schiele. His self-portraits in the book, many of which expressed, as you were saying here, this eroticism, this anxiety. In the case of Self-Portrait with Striped Armlets, it depicts him as a fool. He depicts himself as a fool. So his anxiety may very well evoke this fear in the beholder, or the viewer. But there’s a difference between what Schiele experienced and what he chose to express. So it’s possible that he may have exaggerated or distorted.

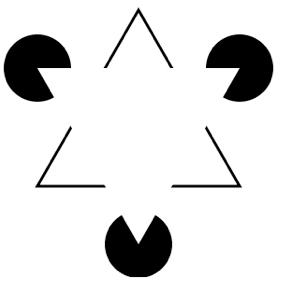

Correspondent: Sure. Well, let’s talk about Egon Schiele. His self-portraits in the book, many of which expressed, as you were saying here, this eroticism, this anxiety. In the case of Self-Portrait with Striped Armlets, it depicts him as a fool. He depicts himself as a fool. So his anxiety may very well evoke this fear in the beholder, or the viewer. But there’s a difference between what Schiele experienced and what he chose to express. So it’s possible that he may have exaggerated or distorted. Correspondent: The key element in assessing the relationship between art and neuroscience is the beholder. Now Semir Zeki has argued that the Kanizsa triangle, where we see these three…

Correspondent: The key element in assessing the relationship between art and neuroscience is the beholder. Now Semir Zeki has argued that the Kanizsa triangle, where we see these three…