On Tuesday night, the 79-year-old Elaine May made a rare 92nd Street Y appearance, spending forty minutes poking at a severely undermatched bird who made the mistake of confessing that he didn’t have a whit of creative writing talent.

“Are you, like, an interviewer?” asked May.

The man may as well have told May that he was an alcoholic sitting at a bar doing his best not to order a drink. He confessed that he was a curator for the Museum of the Moving Image and that he wrote reviews and programmed films. “New films for a museum?” asked May, doing the best she could with this third-rate Nichols stand-in.

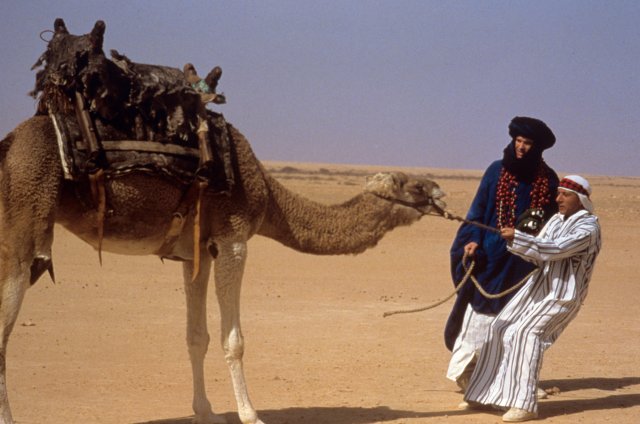

May, a trim presence in a dark two-piece pantsuit, was on stage to discuss Ishtar — the last feature film that she directed. The movie was an homage to the Hope-Crosby Road movies, with Dustin Hoffman and Warren Beatty playing two washed-up songwriters who head to Morocco for a gig and get involved with a woman on the run, a CIA agent played by Charles Grodin, a blind camel, and gunrunners. The film had been a critical and commercial disaster upon its 1987 release (Roger Ebert called it “a lifeless, massive, lumbering exercise in failed comedy”. It has since garnered its share of defenders over the years — including The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody, who has declared Ishtar “among the most original, audacious, and inventive movies—and funniest comedies—of modern times.”

As the director’s cut of Ishtar played, the crowd was split evenly between rabid fans who felt obliged to titter at every moment (even the moments that weren’t intended to be funny) and those who watched with a quiet yet somewhat disappointed curiosity.

David Schwartz — the dopey interlocutor who wanted May to discuss how certain aspects of her work were “part of the discovery” and who offered such profound insights as “you really feel that these two are meant to get together” — didn’t have the guts to follow up on some of the more pivotal topics, such as the kind of material that might have lured May back to the director’s chair. “You have to be offered a movie that’s worth your time,” said May. “And I haven’t been.” Schwartz was too timorous to pursue further.

Judging by the precise manner in which May outlined her science of comedy (“If you’re going to do a a funny scene when someone gets killed, the gun jams. The finger gets stuck in the trigger…”), it appeared that the reticent May was eager to talk about comedy rather than be subjected to vapid adulations. “It’s hard to know how to respond to a complaint, isn’t it?” said May halfway through the colloquy. If there was a slight hauteur to her answers, there was also a carefully concealed humility. She seemed genuinely touched that so many people came, even underreporting the audience tally.

“Either you like the movie or I’m very sick,” she said minutes after the curtain went up.

When asked what she thought of the film now, May replied, “I thought the mix was off. That’s really all you think. I thought it was funny. I think of those people who try out for American Idol.”

Of Ishtar‘s songs, most of them written by Paul Williams, she was proud to point out that she had written the worst of the bad lyrics.

May also alluded to a run-in with Ronald Reagan. “I met him,” she said. “He’s an amazingly naive person. A charming guy who really cared about show business.” Reagan apparently knew the Nichols-May albums so well that he could recite all the lines. “He did the telephone routine. And he was the President!”

May offered some thoughts on Ishtar‘s use of animals. In one scene, Dustin Hoffman’s supine form in the sand attracts vultures. Hoffman agreed to be slathered in raw meat to ensure that enough birds would come. As for the camels, May said, “We tried camels out. A lot of camels came.” She did not elaborate on whether any of these camels made their way to the dinner table, but had mock prognostication at her disposal. “Do they eat camels?” she asked. “Yes, I guess they do.”

May insisted that Ishtar‘s harsh reception had much to do with David Puttnam replacing Guy McElwaine as Columbia’s head of production. Puttnam had produced Chariots of Fire, a film that competed in the Oscar race against Warren Beatty’s Reds. This led Puttnam to harbor resentment towards Beatty during the making of Ishtar. May claimed that Puttnam had called Beatty “self-indulgent” and said that he “should be spanked.” May claimed that Puttnam targeted Isthar in an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times. (I’ve been unable to locate the op-ed in the Los Angeles Times archive, but May may have been referring to a lengthy Tina Brown profile that appeared in Vanity Fair. This helpful David Blum article from New York Magazine contains additional details.) Mike Nichols had said of Puttnam’s actions that this had represented “an entire studio committing suicide.”

May suggested that much of the hostile press notices had to do with Puttnam planting items, especially in relation to how much Ishtar cost. The continued fixation on Ishtar‘s budget apparently was enough to unsettle Charles Grodin, who once shouted to an audience, “What do you care? It’s not your money. It’s Coca-Cola’s money.”

Puttnam didn’t stay with Columbia much longer after Ishtar. May said that he tried to do the same thing to Bill Murray and Bill Cosby. “So they threw him out.”

“If half the people who had made cracks about Ishtar had seen it,” said May, “I would be a rich woman today.”

The original title for the film was to be Road to Ishtar, but Beatty rejected it. May was careful to point out that there was no improv in the film, except when Hoffman and Beatty were making up lyrics at the beginning and during a scene in which Hoffman plays an auctioneer. “You can’t really improv a joke,” said May, “because it has to do with the way it’s worded. Most comic movies aren’t improv. You hope stuff happens.”

May came into film directing entirely by accident. When she wrote A New Leaf, she had merely sought directorial approval. When her manager Hilly Elkins told her that Carol Channing was up for the part that she would play, pointing out that the studio wouldn’t give her approval but would let her direct, she decided to do it.

On A New Leaf, May claimed to confuse one of the big lights for the camera. But because she relied on a meticulously planned shot list, she was surprised to find herself four weeks ahead of shooting schedule. When the editor informed May that some scenes were too long and that she didn’t have any coverage, she adjusted her directorial style and was four weeks behind schedule. Of the “big corporate guy” who gave her the okay, May responded, “How he let me do this, I have no idea.”

May said that she was more frightened during her third time behind the camera than her first time. “If you screw up enough,” she said, “you really learn a lot.” Is there a difference between directing comedic scenes and dramatic scenes (such as the ones contained in Mikey and Nicky)? Not really, but details matter more in comedy. “If you do what would happen in life, it will still be a mess and it becomes funny.”

There were a number of quick questions from the audience.

Warren Beatty: “He’s a Southern boy”

The Heartbreak Kid: “I didn’t see the remake.”

Tina Fey: “I think she’s terrific.”

Does she see movies today? She sees many and especially liked The Hurt Locker.

She mentioned that some actors had recently asked her what she was doing. She replied, “Nothing.” But this was akin to announcing that you havecancer. “No one had ever said, ‘Nothing.'” May is compelled to work these days when hired for scripts (“a good way to work”) or when she happens to write a play.

Of course, an event like this isn’t organized unless there’s a very good marketing reason. There have been past rumblings about Ishtar getting a Blu-ray release, but May revealed that Sony told her that they didn’t have a Blu-ray film to show. The audience last night was shown a so-so print (although I can report that the red headbands worn by Hoffman and Beatty made a serious impression). This suggests very highly that a transfer has not yet been made and that much of the online conjecture — most of it promulgated by aging lunatics harassing Warren Beatty, Sony, and various people who work for Mike Nichols — is unsubstantiated.

“I read on the Net that the impending release of Ishtar had been delayed by my people,” said May. “I was so thrilled to learn that I had people.”

May was carefully to clarify that she was not a profound Hollywood player. “So to some degree,” she said, “they don’t tell me anything.”

Will Ishtar be released on Blu-ray or DVD?

“They say they want to,” said May. Maybe it will “if you all clap your hands and believe in them.”

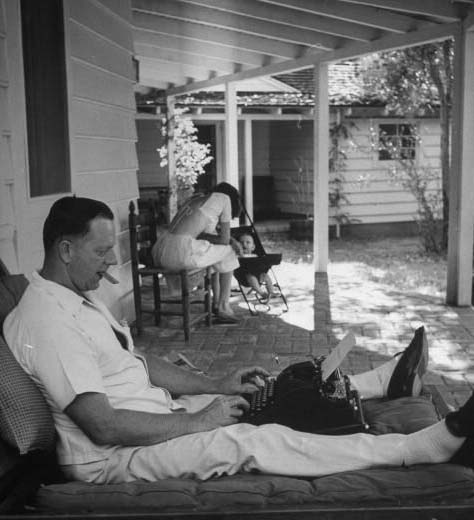

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.