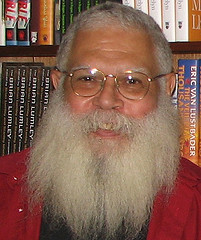

Daniel Woodrell is most recently the author of The Maid’s Version.

Author: Daniel Woodrell

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Twists within Woodrell’s fiction, Thelonious Monk, mysterious narrators, William Kennedy’s Albany Cycle, The Flaming Corsage and Very Old Bones as deeply underrated novels, the snapshot montage approach to presenting history through fiction, how general observations identify people who lived 85 years before, the cemetery as the ultimate marker of memory, the novelist’s obligation to history, why it’s important to explore perspectives foreign to your own, Tomato Red as the creative turning point for Woodrell, the close connections between heightened language and heightened perspective, how respect for a town manifests itself in unusual ways, Ozark vernacular, referring to a cop as “John Law,” “Parmesan” vs. “sprinkled cheese,” consulting the OED, food in Woodrell’s novels, tasty variants of Depression stew, fatback, what people get wrong about stew, hack stew, prostitution, how Woodrell cultivated his knowledge of hookers, junior high school crushes who turn into hookers, people who manipulate others, knowing most of humanity by living in a small town, why there isn’t street crime in the Ozarks, crime that occurs among acquaintances, criminal strangers who lurch into tough guy mode, fighting against the cliche of the guy who wants an easy fight in a small town, Tony Danza’s boxing skills, why it’s important to lose fights, testifying against your cousin, how to create distinctive characters, Plug’s character in The Maid’s Version, families who accept aberrant behavior within kin, not prying into other people’s business, regional literature defined by acceptance of strange behavior, how reading Southern literature tilts real-life concerns, feeble attempts to deny knowledge of William Faulkner, the appeal of Cormac McCarthy’s darker novels, The Bayou Trilogy, Ed McBain’s Isola, how home life is defined in Woodrell’s novels, being more aware of the exterior of homes rather than the interior, reading novels as a way of knowing other regions, Comte de Lautréamont’s knowing narrator style, how illusion creates energy, the urge to feel uncertain, how shaky sales creates creative freedom, the decline of book review sections, why publishers believed in Woodrell with a terrible sales track, disasters and population ratios, the effect of a dance hall explosion on a small town vs. the Boston Marathon bombing, when larger cities don’t always comprehend the impact of disasters, why small towns permit more speculation than metropolitan clusters, the comforts of seemingly conscious forces, grief and belief culture, Woodrell’s abandoned San Francisco novel, why San Francisco didn’t work as a setting for Woodrell, Eddie Muller and the Noir City Film Festival, the joys of film noir, Woodrell’s Vietnam novel, Woodrell’s past experience as a Marine, antiwar protests, growing to accept the necessity of certain types of civil disobedience, false promises from the military, and fiction writing and political impulses.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: We’ve seen twists in your books before. I think of the brutal Civil War swap that opens up Woe to Live On. I think of the relationship revelation after that house break in Tomato Red. But in this book [The Maid’s Version], you have been extremely opaque about the narrator’s identity to the point of, I will confess, mild frustration. But then I started to get into what you were doing. I’m wondering why this opacity, along with the fragmented sense of history, more your style this time around. I’m wondering if this was a formal exercise to see how much material you could pack into a 165 page novel.

Woodrell: Well, I didn’t want to turn it into being about him so much directly. I wanted him to be in a position to know a lot of things and to observe things and to report things. In many ways, this book has a style that would fit nonfiction. Quite a bit of it. And that was also by design. Because I had felt that he was trying to relay fiction. And so I wanted him to be a little bit outside. He’s not the most important person in the book, or even very important. Just as a messenger of the story. And I did really wrestle with this book in terms of what size to make it. I tried to initially make it a big fat one and include everyone in it. It just got out of shape so badly that I essentially threw it away. I eventually realized, “Just The Maid’s Version. Just get down to the bone. To the part that really matters to you.” Or as Thelonious Monk once said, “Just play the notes you really mean.” And I kind of took that to heart here. Just played the notes I really meant.

Correspondent: When you say this was going to be “a big fat one,” what were the original drafts looking like? I mean, you say that you were reporting here. And I’m wondering, given the economy of the final product so to speak, how expansive did you get here?

Woodrell: Well, there were a lot of different rumors about what may have or may not have happened. There were a lot of different players who could have come into the picture briefly or at more length. Even the little bios of some of the victims were originally quite a few pages a piece. And it began to lose shape and focus and it wandered too much for me. And that’s a little bit depressing sometimes. When you get to page 100 and something and you say, “I think I can use ten of these.”

Correspondent: By the way, can we actually confess the narrator’s name? I guess we can.

Woodrell: Yeah. His name is…

Correspondent: Alek.

Woodrell: Alek. He is named a few times.

Correspondent: He is. He is. I didn’t know the extent of spoilers. I’ve seen reviews do this. So he’s Alek. Out of the bag.

Woodrell: And there have been people who read it and didn’t catch his name. They didn’t know he had a name. No, he is named.

Correspondent: Yes.

Woodrell: It didn’t occur to me. (laughs)

Correspondent: Did this book start with Alek? How did the reporting and how did the wrestling with history become such a part of this book? We can talk about the fire that is actually a real dance hall fire in 1928 that is also in this book. So what caused your imagination to wander into this factual milieu?

Woodrell: Well, I’d heard about this ever since I was old enough to be told this kind of detail. And I eventually began to learn there were a lot of versions or rumors about what might or might not have happened. And the very first time I attempted to get into this, it was omniscient and there was no Alek and there was no particular focus on the Dunahew family. It was going to be pretty tightly — there was a Wiliam Kennedy book I liked. A lot of other people didn’t seem to.

Correspondent: Which one? Very Old Bones?

Woodrell: The Flaming Corsage. And Very Old Bones. Both of them.

Correspondent: Very Old Bones, I feel, is very underrated.

Woodrell: I think it is too. I really like that. I love Kennedy. Period. So I’m not really capable of being unbiased toward him. But I liked that a lot. And I felt like it moved a certain story through history rather well and it certainly kept me going.

Correspondent: So his montage nature, I think, in that book appealed to you for this?

Woodrell: Yeah. It did.

Correspondent: That’s interesting. That totally makes sense.

Woodrell: So originally it was going to be here’s the maid for a minute and then here’s someone else and here’s someone else, and they’re all linked together. And the story would expand from there and go forward. But slowly over a period of time, I realized that the personal part of it, the Dunahew family’s interior relationship to this, was fundamental to me really. I just hadn’t recognized how important that part of it was to me. And it began to seem to me that that was the way to go into this.

Correspondent: I’m curious. At what point did the dance hall start to inform the snapshot approach? Was it more the dance hall? Or the Kennedy book The Flaming Corsage?

Woodrell: Well, you go around town talking about the real event, you get little snippets. And a number of the victims are remembered by one thing that was notable about them or that was often reported. “She played the piano” or “He was a good ballplayer.” Or something like that. And so over a period of time, these characters, as they’re discussed, are sitting around time with other citizens. They begin to have the one, two, or three things that have stuck about them in the minds of the people there. And I began to realize, “Yeah, that’s right. There are certain essential qualities of people that linger for 85 years. They should live here.” So that kind of informed those. And I definitely wanted the victims to be brought forward somehow. And I didn’t want it all to just be thirty-five people walking toward the dance or something like that.

Correspondent: Sure. So you felt a responsibility to imbue the victims with some kind of identity as opposed to being random names. This brings me to the cemetery, which forms a serious part of this book. I mean, Alma always ends her walks there, we learn at the very beginning. But then we learn about the dance hall owner, whose past is actually revealed through the cemetery. A lot of his associations. And I was wondering first and foremost, well, did you wander around the cemetery yourself looking for leads here? Or was this kind of a way for you to remind both the readers and also to imbue the town with additional life? I mean, here is this marker of memory. All these people have died. And you can’t escape your legacy. I mean, what was the appeal of this?

Woodrell: Well, by an accident of just chance, a fair portion of my family are buried only about fifteen feet from the memorial. So all my life, when we’d go over to put the flowers down for Memorial Day and so forth, I’d think, “What’s this?” And then slowly that would develop. And then also, by happenstance, a number of the people who were identified are also buried near there. That was the section of the cemetery that was then being filled. So as I began learning more and more of the names of the people who were actually relevant to the event, I began to realize, “Oh! They’re all planted around here.” So that very fact resonated with me. I’m not…I never say what happened. Because I don’t know what happened. I chose a story that really rang for me and went with it. But I could walk around town and find a number of people who are still debating a lot of different angles that I never really suggested.

Correspondent: This leads me to ask. What obligation do you really have to history? I mean, this isn’t your first historical novel. You explored the Kansas Irregulars in the Civil War novel. In this, you’re dealing with something that’s a little bit more local than that — and also your family history. I mean, the Civil War — even the Kansas Irregulars — offers a really wide canvas for the imagination to bristle. But in this, you’re dealing with something that is so hyperlocal that I wonder if you have any problems bending the truth as fiction requires or whether you run with the actual basis and let things go into place from there.

Woodrell: Well, none of the people who were allegedly in the periphery of this or maybe even toward the center of it appealed to me as members of the community and as historical figures, but not as fictional characters. I didn’t feel drawn to write about people with some of the characteristics that these rumored individuals actually presented. And I specifically didn’t want to write about the wealthy in town sitting around twisting their mustaches thinking of villainy to perpetrate upon the lower classes.

Correspondent: Was there a real banker?

Woodrell: There was a banker who was sometimes mentioned as having had something involved maybe. But he was a much more dangerous kind of guy and a relentless skirt chaser and all that. Not the character that I found myself writing about. It was in the same way that I ended up writing about the Southern bushwhackers instead of the Northern [in Woe to Live On]. I had originally started out to write a book about the Northern. And then I realized that that was actually a little too easy for me to inhabit that sensibility. And it was more of a stretch for me politically and as a person to try to get inside the other side and what was making them tick. So I wanted this character to be someone that it would be more of a surprise if he were accidentally or purposely involved in something.

Correspondent: So part of the appeal of The Maid’s Version and all these little bits and anecdotes you were collecting was to really inhabit the Other. In this way.

Woodrell: Yeah. As time went on, I realized more and more it’s the key to the whole book — to me anyway. It’s the Dunahew family story. That the dance hall and some of the surrounding qualities of that or aftereffects of that were propellants to the Dunahew family’s shift over a generation and a half or two.

Correspondent: I actually really wanted to ask you about a tilt in your writing style that I detected with Tomato Red, where suddenly you have sentences that demand almost this total life through language. Of course, a lot of this is evident because of that amazing first paragraph in Tomato Red, but I wanted to point it out by reading one of the sentences from Tomato Red: “This Pinto pooted small gray distress signals from the tailpipe and sounded like a chain-smoker at a cold dawn and practically shrieked for a civil rights lawyer when I forced it up hills.” So aside from the simile, we have “Pinto pooted.” We have “up hills” split into two words. I’m wondering, with this book, did you need to have that voice of Sammy Barlach to just really get these sentences? Is perspective really the way for you to evolve as a stylist? I was hoping to get something.

Woodrell: Yeah. Very much. And Sammy was probably the first voice I did that was quite — he’s not unhinged or anything, but he definitely sees everything from a little bit of a different angle than most of us probably do. And I thought of Sammy very much as an Expressionist. He’s looking at the real world but he’s just not seeing it exactly the way most people see it. And so that began to suggest a richness of language because of the insights he was having that kind of called for that. And it wouldn’t be any fun for me to write if I wasn’t allowed to let the language run amuck and then hopefully, if it’s really amuck, I’ll catch it in time to trim it back. (laughs) But that’s a big motivating force for me to write at all.

Correspondent: I was wondering if that was the aha moment for you. I mean, I like the other books before that. But that one really amps things up to this level where the language and the character are absolutely one in a way that it continues with the subsequent books. And it’s interesting that with The Maid’s Version, you go to this more succinct approach to also try and inhabit the sentence. Did the structure of this book — was it almost an obstacle for the language perspective approach? I was wondering about that.

Woodrell: Well, Tomato Red — and I would agree with you on that. I have often said that I felt that something started to click there. I wasn’t fully cognizant of just what all was going on. In fact, it was only when I had an occasional look at it maybe a year after I’d finished it, I began to recognize more of what was going on in there. And in this book, I didn’t want one character to tell the story in such a forceful way that they precluded all other possible interpretations or something. That it was just so forcefully about them that they would overshadow everything else. And that’s part of the reason why Alek is a little to the side. It’s also a book where I have a bunch of, you know, “motherfucker this motherfucker that.” And it wasn’t really on purpose initially. And then I was reading through it and I realized, “Oh! Where’s your standard?” (laughs)

Correspondent: I think though that the respect for the grief of this town is probably what motivates that. And maybe, it would seem to me anyway, that what you’re trying to do language-wise with this was to give voice to the town as opposed to one solitary perspective. Is that safe to say?

Woodrell: Yeah. And people are introduced as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” A generation and a half or two ago almost, that would be standard. The lady next door was not Joan. She was Mrs. Henry Eastall. And that suggests a certain kind of decorum and regard and circumspection.

(Loops for this program provided by vlalys, danke, maikeeelx, and megapaul.)

The Bat Segundo Show #517: Daniel Woodrell (Download MP3)