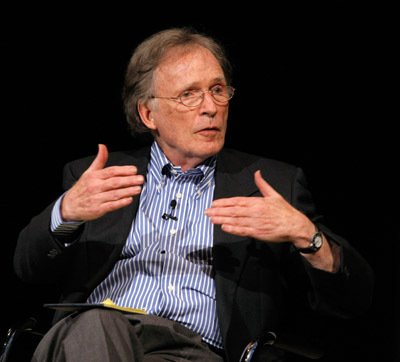

John Waters appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #342. Mr. Waters is most recently the author of Role Models.

(Considerable gratitude to Wayman Ng, who resuscitated this conversation from the data grave.)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Comparing himself to unspecified reference groups in Mertonian social situations.

Author: John Waters

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: You observe that listening to what Tennessee Williams has to say could save the reader’s life too. But how can Tennessee Williams save the life of, say, a humorless tax auditor?

Waters: They won’t read him. So I’m not saying he can save anybody’s life. But if the humorless tax auditor — and I actually know one tax auditor who does have a sense of humor.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Waters: If they read Tennessee Williams, maybe they could save their life. Maybe they would overlook one receipt that wasn’t exactly deductible for business if they thought the person was doing art.

Correspondent: Yeah. That’s true. In Role Models, you note that you drink every Friday night. Now in Crackpot, you observe that in your final year of smoking, you smoked only on Fridays.

Waters: Yeah.

Correspondent: Why would you confine vice to one day of the week?

Waters: Well, because the cigarette thing. Didn’t smoke. I used to. I haven’t smoked in — I write it down every day. I could tell you how many days. I’d have to look at my file card. But today — and even before then, I only smoked for three days. I fell off the wagon. But when I smoked every Friday night, it got to be — I couldn’t do that. Because at Thursday night at 11:59, I would light up and hotbox. Do you know what that means? Where you take one drag on a cigarette burn.

Correspondent: Oh yeah.

Waters: A carton! Like right in a row. So I learned that I can’t chip. I am an addict with cigarettes. So that’s why. Friday nights? Because I don’t work on Saturday. And every other ngiht’s a schoolnight to me. I write in the morning. I can’t write with a hangover. I can’t. And when I drank on Friday — I did smoking on Friday night because I knew that I didn’t have to work the next day. I was going to drink too. I might as well do it all.

Correspondent: This is your answer to Shabbos?

Waters: No. It’s just how I get through life really. That I’m very organized during the week. And as I said, I believe if you’re going to have a hangover, it should be planned on your calendar three weeks in advance.

Correspondent: But you can’t plan everything.

Waters: I do plan everything.

Correspondent: You do plan everything.

Waters: Everything! I never have a spontaneous moment. I don’t want a spontaneous moment.

Correspondent: Really.

Waters: Order is important to me. It brings me happiness. Which makes my assistants insane.

Correspondent: Really?

Waters: Yeah.

Correspondent: What do you do when a curveball shows up?

Waters: I plan. Well, a curveball? I deal with it. But I’m saying that I won’t not do something that’s going to be great fun because I didn’t plan it.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Waters: But I make sure that I have great fun planned so I don’t wait around for someone to knock on my door and give me great fun.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Waters: I go out to have great fun. And plan it.

Correspondent: Well, how rigidly do you plan your life?

Waters: Rigidly enough.

Correspondent: Are you like a senator?

Waters: Let’s just say…

Correspondent: Do you schedule when you shit? I mean…

Waters: No. But I usually do that around the same time too. And I get on an airplane. And I can adjust my watch to whatever time it is. Get off and be on that time. I’m organized, yes. But if something — you know, when I go out on Friday nights, something can happen. It’s not like I know what’s going to happen. But I have certain people I go with to different places. Because I don’t want to drink and drive. So I have a great pool that I go out with. And they’ll go to any weird bar. You’ve seen the bars I like to go to. There’s a whole chapter on that.

Correspondent: But I’m curious. Do you allot a two hour time to just go out and observe people? Or something along those lines?

Waters: Well, I’m always observing people. It doesn’t matter. On the subway, I’m observing people. I take the bus in San Francisco a lot to observe people. I watch people in airports get off the plane. I make up stories about every person. And if you look, the ugliest people get off first. They aren’t first class. The cuter they are, the worse seats they have on an airplane. It’s awful. It almost is foolproof. I know that sounds ridiculous. The poorest planners. The ones that lasted till the last minute and got the middle seat in the last row?

Correspondent: Yeah.

Waters: They’re cuter than the ones who are rich or smart enough to plan to use their frequent flyer miles to get one of the few seats available in first class. They’re never that good looking.

The Bat Segundo Show #342: John Waters (Download MP3)

Lee: I’ve always been very conscious of language. It might seem silly of me to say, given all of the things that have happened in my books. I’m not terribly interested in plot. (laughs) I mean, I enjoy it. But I find, for me, the real action in drama is in the play of the sentences and in the play of the words. That’s what draws me through the story too. I mean, in some ways, unless I hear the sentence, I don’t understand what it really means. And even back in school, when I was writing a lot more essays, I would always try to craft it so that it felt like something and it sounded like something to me, rather than just said something. And particularly vis-à-vis the scenes of violence, I wanted — I think in this book and in A Gesture Life — I tried to think to myself, “What was the most, in some ways, unlikely way to describe this?” With perhaps spare and beautiful language that would add a layer of a different kind of horror to the moment. Just the contrast between how not lovely, but how handsome everything seemed and normal, given what was happening.

Lee: I’ve always been very conscious of language. It might seem silly of me to say, given all of the things that have happened in my books. I’m not terribly interested in plot. (laughs) I mean, I enjoy it. But I find, for me, the real action in drama is in the play of the sentences and in the play of the words. That’s what draws me through the story too. I mean, in some ways, unless I hear the sentence, I don’t understand what it really means. And even back in school, when I was writing a lot more essays, I would always try to craft it so that it felt like something and it sounded like something to me, rather than just said something. And particularly vis-à-vis the scenes of violence, I wanted — I think in this book and in A Gesture Life — I tried to think to myself, “What was the most, in some ways, unlikely way to describe this?” With perhaps spare and beautiful language that would add a layer of a different kind of horror to the moment. Just the contrast between how not lovely, but how handsome everything seemed and normal, given what was happening.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about your sentences. You do something extremely interesting, and this syllabic form of internal rhyme. I’ll just give you a number of examples: “a tawny teen in a cocktail dress of skimpy hemp.” “I started to rub myself and, remembering I would have to retrieve Bernie soon, recalled that I’d once done what I was doing with Bernie in the room.” So there’s the oo, oo. The book’s opening line, of course: “Horace, the office temp, was a run-down and demented pimp.” So I’m curious whether these particular sounds serve as, I suppose, reference points in your mind to get a sentence right, whether this came from your previous career as a lyricist or possibly the Gordon Lish school rubbing off now after so many books and the like.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about your sentences. You do something extremely interesting, and this syllabic form of internal rhyme. I’ll just give you a number of examples: “a tawny teen in a cocktail dress of skimpy hemp.” “I started to rub myself and, remembering I would have to retrieve Bernie soon, recalled that I’d once done what I was doing with Bernie in the room.” So there’s the oo, oo. The book’s opening line, of course: “Horace, the office temp, was a run-down and demented pimp.” So I’m curious whether these particular sounds serve as, I suppose, reference points in your mind to get a sentence right, whether this came from your previous career as a lyricist or possibly the Gordon Lish school rubbing off now after so many books and the like.

Johnson: The Internet is in the library. Google is in the library. The librarians know how to use that. So you go to those public computers in the library. You have a librarian who can not only do Google, but who can also tell you, point you to any number of other resources that are not included in Google, or that are very difficult to get to through Google. It seems like Google is so simple. “It’s so simple even your grandmother can use it,” is the way it was described to me. Yeah, it’s brilliant for getting the quick hit on the restaurant in the Village that you want to have dinner at. There’s the address. There’s the phone number. There’s the little Google map that will get you there. But when you are actually trying to track back. When I have a clipping of a newspaper, and I’m trying to find the digital version of that, I get lost sometimes. It can’t find it. The bread crumbs don’t take you to where you know it has to be. And I’ve had librarians who have actually shown me how to wend my way through Google, which is, after all, full of redundancies, not weighted in terms of date. You need to put your heavy boots on to wade through it sometimes.

Johnson: The Internet is in the library. Google is in the library. The librarians know how to use that. So you go to those public computers in the library. You have a librarian who can not only do Google, but who can also tell you, point you to any number of other resources that are not included in Google, or that are very difficult to get to through Google. It seems like Google is so simple. “It’s so simple even your grandmother can use it,” is the way it was described to me. Yeah, it’s brilliant for getting the quick hit on the restaurant in the Village that you want to have dinner at. There’s the address. There’s the phone number. There’s the little Google map that will get you there. But when you are actually trying to track back. When I have a clipping of a newspaper, and I’m trying to find the digital version of that, I get lost sometimes. It can’t find it. The bread crumbs don’t take you to where you know it has to be. And I’ve had librarians who have actually shown me how to wend my way through Google, which is, after all, full of redundancies, not weighted in terms of date. You need to put your heavy boots on to wade through it sometimes.

Correspondent: I wanted to go back to the hair. I had alluded to that earlier. It could just be me, but you do have a concern for hair. It’s often quite specific, as I suggested. You begin “Amber at the Window in Hurricane Season” by describing her pushing “a blond lock behind her ear, stray hairs glancing off a steel row of studs.” In “In My Heart I Am Already Gone,” you describe how Vicky “cuts her own bangs, a ragged diagonal like the torn hem of a nightgown.” In “Weekend Away,” the hitchhiker has “black, messy hair mostly covering his ears.” In “What Was Once All Yours,” Cass has hairy forearms. I’m curious about this hair. And also we haven’t alluded to the cat as well. Is it more of a protective element? You know, these characters are often barren against the elements, so to speak. And I’m curious about this. You are a hair man, I have to say.

Correspondent: I wanted to go back to the hair. I had alluded to that earlier. It could just be me, but you do have a concern for hair. It’s often quite specific, as I suggested. You begin “Amber at the Window in Hurricane Season” by describing her pushing “a blond lock behind her ear, stray hairs glancing off a steel row of studs.” In “In My Heart I Am Already Gone,” you describe how Vicky “cuts her own bangs, a ragged diagonal like the torn hem of a nightgown.” In “Weekend Away,” the hitchhiker has “black, messy hair mostly covering his ears.” In “What Was Once All Yours,” Cass has hairy forearms. I’m curious about this hair. And also we haven’t alluded to the cat as well. Is it more of a protective element? You know, these characters are often barren against the elements, so to speak. And I’m curious about this. You are a hair man, I have to say.

Correspondent: What was it about the radio school instructor’s body language that suggested “a few divorces in his past?”

Correspondent: What was it about the radio school instructor’s body language that suggested “a few divorces in his past?”

Grafton: I don’t like to repel readers. I mean, we’re always dealing with homicide and violence of this sort, which is difficult enough. I don’t want to rub that in my reader’s face.

Grafton: I don’t like to repel readers. I mean, we’re always dealing with homicide and violence of this sort, which is difficult enough. I don’t want to rub that in my reader’s face.

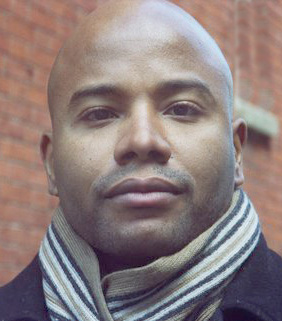

Correspondent: When Malcolm X delivered

Correspondent: When Malcolm X delivered

Correspondent: I wanted to ask about the many interesting aspects of candymaking that are throughout this book. Alice herself says that most candy factories have very tight security. You, I know, did some research. And I’m wondering how you managed to get many of these morsels into the actual book, and whether a lot of this is fabricated and a lot of this is speculation.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask about the many interesting aspects of candymaking that are throughout this book. Alice herself says that most candy factories have very tight security. You, I know, did some research. And I’m wondering how you managed to get many of these morsels into the actual book, and whether a lot of this is fabricated and a lot of this is speculation.

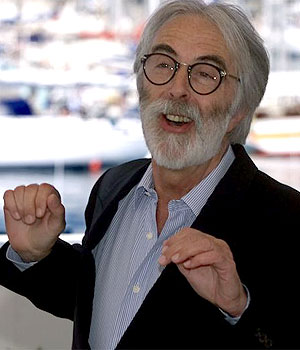

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?

Correspondent: There’s one question that is presented in the book, but never actually quite answered. It’s probably something I just observed. And that is Google’s fixation with the number 150. They have 150 projects. They have cafeterias and conference rooms that are max 150. Did you ever get an answer as to why they were obsessed with this number? Numerologists?

Correspondent: There’s one question that is presented in the book, but never actually quite answered. It’s probably something I just observed. And that is Google’s fixation with the number 150. They have 150 projects. They have cafeterias and conference rooms that are max 150. Did you ever get an answer as to why they were obsessed with this number? Numerologists?

Correspondent: In light of Armstrong’s remarks about the Little Rock Nine, and of course his infamous remarks about Eisenhower, did the guy have an FBI file? Were you able to…?

Correspondent: In light of Armstrong’s remarks about the Little Rock Nine, and of course his infamous remarks about Eisenhower, did the guy have an FBI file? Were you able to…?

Correspondent: Do you need to have a source text more than, I suppose, a personal experience? I mean, I could inquire as to whether you had sex with a mime. I don’t know whether you have or not.

Correspondent: Do you need to have a source text more than, I suppose, a personal experience? I mean, I could inquire as to whether you had sex with a mime. I don’t know whether you have or not.

Correspondent: You mentioned that you had attempted memoir before.

Correspondent: You mentioned that you had attempted memoir before.

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Correspondent: I’m curious about this period of you coming to New York. Coming into town. You’re on the prowl trying to get work as an actor. Before you eventually become a copy boy for Time Magazine.

Correspondent: I’m curious about this period of you coming to New York. Coming into town. You’re on the prowl trying to get work as an actor. Before you eventually become a copy boy for Time Magazine.

Estep: “Our love of animals is directly proportionate to our indifference to human beings.” It’s a little bit of an exaggeration. I grew up around all sorts of horses and cats and dogs. To this day, my mom — if I want to get her talking to me for more than two minutes — it has to be about the dogs. So it’s an off-the-nose dialogue where we’re talking about the dogs. But really we’re talking about something else.

Estep: “Our love of animals is directly proportionate to our indifference to human beings.” It’s a little bit of an exaggeration. I grew up around all sorts of horses and cats and dogs. To this day, my mom — if I want to get her talking to me for more than two minutes — it has to be about the dogs. So it’s an off-the-nose dialogue where we’re talking about the dogs. But really we’re talking about something else.

Correspondent: Reading this book, I got the sense that the three Ps — pandemic, pestilence, and what’s the other one? plague! — that we’re essentially overstating them. But I want to start off by offering a hypothetical scenario. If I’m sitting at a restaurant, and a Norway rat jumps onto the table and starts nibbling at my sandwich, I’m going to have some understandable concerns. So I guess the question is, if we are in a culture of needless dread about the three Ps, what is the amount of fear that is acceptable for you? Some general terms.

Correspondent: Reading this book, I got the sense that the three Ps — pandemic, pestilence, and what’s the other one? plague! — that we’re essentially overstating them. But I want to start off by offering a hypothetical scenario. If I’m sitting at a restaurant, and a Norway rat jumps onto the table and starts nibbling at my sandwich, I’m going to have some understandable concerns. So I guess the question is, if we are in a culture of needless dread about the three Ps, what is the amount of fear that is acceptable for you? Some general terms.

Skurnick: You know, you make up a story for what you’re trying to do later, but who knows what you were trying to do?

Skurnick: You know, you make up a story for what you’re trying to do later, but who knows what you were trying to do?

Correspondent: But the writing that you did. The times that you had. Surely now, decades later, you remember those times. They matter more to you than the brand name on that sneaker. And not only that. But it seems to me that you had a situation. I had a similar situation in terms of having hand-me-downs and that kind of thing.

Correspondent: But the writing that you did. The times that you had. Surely now, decades later, you remember those times. They matter more to you than the brand name on that sneaker. And not only that. But it seems to me that you had a situation. I had a similar situation in terms of having hand-me-downs and that kind of thing.

Mieville: Fundamentally, what this is about is taking the logic of everyday borders — the logic of political boundaries — and extrapolating them just a little tiny bit. But the logic is the same. It’s an exaggeration, but it’s not a radical break. So in terms of the rules of physics and all that sort of stuff, it is at least 96% sure that they are the same as in this world here. This is not a magical realm in that sense. That’s not how this works. And that’s quite a big difference. Because that short story [“Reports of Certain Events in London”] was very much about the kind of implicit dream logic of the psychogeography of London, and literalizing that metaphor and the city as an uneasy beast. This is slightly different. In some ways, this is much more to do with a genuine juridical legal reality of the world. As I said, it’s extrapolated. But to that extent, it’s very realistic. The logic of the strangeness is actually a logic that exists in the real world. It’s a little bit exaggerated, but that’s all. So to me, they feel quite different. But that’s not to invalidate your point. Because like I say, it has much to do with reception and subconscious stuff. But at a conscious level, they felt different to me.

Mieville: Fundamentally, what this is about is taking the logic of everyday borders — the logic of political boundaries — and extrapolating them just a little tiny bit. But the logic is the same. It’s an exaggeration, but it’s not a radical break. So in terms of the rules of physics and all that sort of stuff, it is at least 96% sure that they are the same as in this world here. This is not a magical realm in that sense. That’s not how this works. And that’s quite a big difference. Because that short story [“Reports of Certain Events in London”] was very much about the kind of implicit dream logic of the psychogeography of London, and literalizing that metaphor and the city as an uneasy beast. This is slightly different. In some ways, this is much more to do with a genuine juridical legal reality of the world. As I said, it’s extrapolated. But to that extent, it’s very realistic. The logic of the strangeness is actually a logic that exists in the real world. It’s a little bit exaggerated, but that’s all. So to me, they feel quite different. But that’s not to invalidate your point. Because like I say, it has much to do with reception and subconscious stuff. But at a conscious level, they felt different to me.

Correspondent: You bring up Gresham’s law a few times in the book. That principle in which bad money drives out the good. Your example involves watered down milk over purer milk. But as you point out both in the book, with the idea of Americans having less spending money for T-shirts and lettuce, and in this particular idea that you just said in your last answer about looking for the ultimate bargain, if we have indeed become accustomed to our watered down milk, why then would we start accustomizing ourselves to purer milk? Or this higher aspect of craftsmanship? If there is no economic incentive for us to do so, then surely are we trapped in this cycle of bad money driving out the good?

Correspondent: You bring up Gresham’s law a few times in the book. That principle in which bad money drives out the good. Your example involves watered down milk over purer milk. But as you point out both in the book, with the idea of Americans having less spending money for T-shirts and lettuce, and in this particular idea that you just said in your last answer about looking for the ultimate bargain, if we have indeed become accustomed to our watered down milk, why then would we start accustomizing ourselves to purer milk? Or this higher aspect of craftsmanship? If there is no economic incentive for us to do so, then surely are we trapped in this cycle of bad money driving out the good?